help from Zina I. Ivanova- Unarova, Yakutsk State U.

dedicated, with great respect, to Vladimir Kh. Ivanov-Unarov

Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer, Research Professor, Georgetown University;

Research Fellow, American Museum of Natural History

SHAMANIC OBJECTS, MUSEUM COLLECTING AND HARBORING

ABSTRACT:

Does the American Museum of Natural History cloak or harbor sacred objects from its renowned late 19th- early 20th century Jesup collection? The museum’s main role is saving objects for public marvel, rather than hiding them for posterity. Available to an increasingly multicultural audience, to cyberspace and to scholars, including indigenous Siberians eager to visit their lost heritage, these objects, very likely saved from Soviet period destruction, have become treasured symbols of a revitalizing process. Interaction with the collection on many levels has intensified in recent years. As we study sacred objects using insights of currently active healers and patients, we can see that the elaborate cloaks of many Siberian and Far Eastern shamans reflect the values and symbols of their wearers and communities. Integrated into their suede, fringe and metallic talismans are diverse cosmologies and direct links to spirits of multiple worlds. To be effective, the cloaks are personal, constructed over a lifetime of visions and gifts from patients, and enlivened through ritual. Their resonance enables rethinking of diverse ways spirit-imbued shamanic objects interact with believers over multiple generations.

“Artworks are manifestations of ‘culture’ as a collective phenomenon, they are, like people, enculturated beings.” [and thus relational beings]

Alfred Gell. Art and Agency (Oxford: Oxford U. Press, 1998: 153)

Introduction

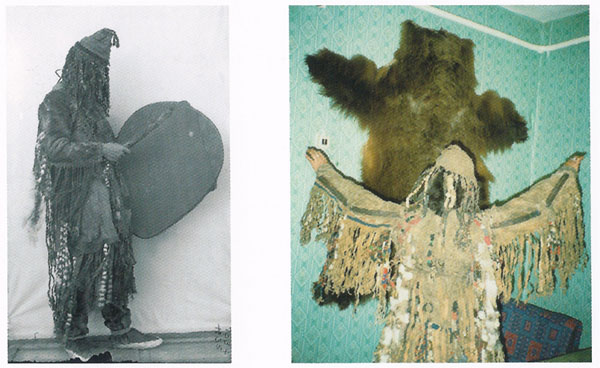

In the mid-1990s, the Yukaghir linguist, Gavril N. Kurilov (pen name Uluro Ado 2005), visited my home from Northeast Siberia, on his way to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York. He was excitedly anticipating seeing the shamanic cloaks that he had heard are kept there, as part of the famed collection of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition. It is possible, he confided, that one set of shaman’s regalia came from ‘one of my grandfathers.’ Rather than wanting to make some claim on it, he wanted to see it for himself, to commune with it, for he felt that the collection, particularly the shamanic cloaks, remained powerful despite all they had been through to get to New York. (See photo 1.)

Photo 1: Yukaghir shaman in ceremonial dress. Jesup North Pacific Expedition, AMNH photo 1835, by W. Jochelson, 1902. Note also Shaman’s Cloak, Yukaghir. Jesup North Pacific Expedition AMNH, collected by W. Jochelson, catalogue number 70/ 8440. Made of fur, hide, cloth, sinew metal, bead. Shaman’s apron is number 8441, hat is number 8341, with same accession number 1902-90.

A second revealing story comes from working with Alexandra K. Chirkova periodically since the early 1990s. Alexandra Konstantinova is at once a certified Sakha (Yakut) medical doctor with a European (Moscow) medical degree and a folk healer. She is the daughter of one of the greatest Sakha shamans of the 20th century, Konstantin oiuun, and he left his shamanic cloak to her, with elaborate instructions as to how it should be kept from her until she was spiritually ready to receive it. By 1993, when I first visited her in the town of Belaia Gora, where she was the head doctor in the hospital, she was using the cloak privately to cure herself. She put it on when she got terrible headaches and felt immediate relief. One evening, she took the cloak from its special hiding place, and gingerly opened it out to show me. It was magnificent – as elaborate a shamanic outfit as I had ever seen – and more filled with symbolic objects (such as prized bird pendants, metal plates, ribbons, beads, bells and bird-like fringe) than most I had seen in museums in either AMNH or St. Petersburg.1 Alexandra, as she put it on, explained that many of the dangling metal objects, and other small sewn-on treasures, were gifts given to her father from grateful patients. The meaning of the cloak was intensified over time by the interactive way patients expressed their thanks through personal, symbolic gifts.

While we will never know the full meaning behind such personalized sacred objects, these stories reveal relationships with shamanic cloaks and their accouterments that go beyond the familiar resonance and symbolism of shamanic drums filled with cosmological iconography for spirit calling. They reinforce the significance of continued beliefs, informed by and activated through rituals great and small. They extend the context and meaning of sacred objects beyond the more blatant and ever-fascinating full fledged shamanic seances, that continue today in limited places and situations in Siberia. Sacredness can be negotiated and have ripple effects when major rituals in traditional contexts, such as seances, are no longer possible or convenient.2

The Jesup collection of the American Museum of Natural History is from Far Eastern indigenous peoples (termed Siberians in the U.S. and Europe) of different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds, including the paleo-AsiaticYukaghir, Tungusic Evenk, and Turkic Sakha (Yakut) of present-day Sakha Republic (Yakutia). Ethno-linguistic diversity should not mask a deeply symbolic convergence in the way people treat and revere shamanic objects. Indeed, an initial point to stress is the plural ethnicity within many indigenous communities in the Far East, today and over 100 years ago during the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, wreaking havoc on museum filing systems.3 Patients appealed to shamans across ethnic group ‘boundaries,’ and shamanic cloaks worn by the greatest Sakha shamans (oiuun), like Konstantin of Belaia Gora and Tokoyeu of Kolyma, could be sewn by Even family members and harbored for safe-keeping by Yukaghir friends. People’s personal ethnic backgrounds in these communities were often mixed enough to become less important than basic trust in healing contexts.4

Another relevant concept for understanding the symbolism and use of some sacred Siberian clothing is that shamans and their cloaks often transcended and merged gender distinctions. The form of many of the shamanic cloaks in AMNH and the St. Petersburg collections are similar to Tungusic women’s dresses. They were worn by men and women shamans who during seances, depending on their helping spirits, utilized during altered consciousness the powers of the opposite ‘sex’ in their practices. Whether their powers were blended enough to constitute a ‘third gender’ is debated in the literature. However, talented and effective ‘gender bending’ may be one of several reasons why Tungusic shamans were said to be especially strong in the Far East. (See photo 3. Jesup photos are also in Kendall et al 1997).5

Gender bending Even “Tungus” shaman, Waldemar Jochelson, 1901 AMNH collection 1610, also published in Jochelson 1995: 257, chapter 7, ill. 2.

This presentation explores three major questions. How did explicitly sacred objects come to be in the AMNH Jesup North Pacific Expedition collection? In retrospect, would many of the shamanic objects have been destroyed during the Stalinist anti-religious repressions of the 1930s? More currently, why has the AMNH become one of the landmarks for indigenous scholars and spiritual seekers struggling with cultural revitalization in the Sakha Republic (formerly called Yakutia)? Discussion is informed by the scholarship and insights of my main interlocutor on this project, Sakha art historian Zina Ivanova-Unarova, who with her husband the late Vladimir Ivanov-Unarov was one of the first to make the ‘pilgrimage’ to the AMNH.

Contexts for Dispossession

The history of the formation of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, under Franz Boas at the end of the nineteenth century (lasting from 1897-1902) is well-known and recounted on the state-of-the-art AMNH website. Russian scholars such as Waldemar [Vladimir] Bogaras and Waldemar [Vladimir] Jochelson, contacted via the Royal Academy of Sciences, had been political exiles who became ethnographers, deciding that the local peoples were by far the most interesting aspect of their enforced stay in the Far East. They had some, albeit limited, funds to buy museum objects, and considerable motive to please their American colleagues.6

How did they manage to talk shamans or their kin into giving up their sacred wealth, for any amount of money or vodka? Sakha, Evenk and Yukaghir colleagues and friends have suggested that many indigenous families in the already colonized communities of the Far North were in dire straits by the end of the nineteenth century. This is confirmed by my archival research, from the historical documents of tsarist ysakh (tax) officials and of missionaries.7 Their traditional livelihoods had been disrupted, family hunting and animal husbandry territories curtailed, and dependence on trade goods increased. If they were starving, the temptation to take food, drink, tea bricks, trade goods, and tsarist coins in exchange for sacred objects would have been considerable. In some documented cases, the cloaks and other sacred objects were sold by the children of shamans, after their shaman kin had passed on. In such situations, the objects, made for only one person, were deemed to have enough potential danger to the family to warrant sending them far away.

The Yukaghir shaman who was Kurilov’s grandfather (or great-grandfather?) may have had a way to order another shamanic coat, after giving up his own with tears in his eyes, according to Jochelson’s own account. He also may have been demoralized enough by the perceived power of Russian outsiders to sense that his own spiritual connection with the lovely tasseled and winged cloak was fading. Zina prefers this explanation, and sees the cross-like form smack on its central spine at a strategic, energetically sensitive spot to be a stylized sacred eagle. Another theory (from a similar cloak) is that it is “an adapted Orthodox cross as a vertebral element” (Fitzhugh and Crowell 1988: 297). Some shamans of the North indeed attempted to integrate the perceived power of Russian Orthodoxy into their cosmology. For example, St. Nicholas appeared as a spirit helper/ curer on shamans’ drums. Yukaghir shamanists sometimes carried small icons. What happened when such symbols were perceived to fail in their hoped for functions? Russian Orthodox missionaries in Yukaghir and Even (Lamut) territories of Northeastern Yakutia Gubernaia were few and spread thin, visiting only rarely in their ‘semi-nomadic rounds.’ Many of the indigenous communities of the region were only superficially Christianized, listed with names in Orthodox record books but practicing shamanists. Their wrestling with unfamiliar infiltrating political forces, misunderstood Orthodoxy and new illnesses may have led to disillusionment with spirits (new, old, multiethnic with multiple personalities) deemed not up to the task of coping with the pain of socio-economic transitions.

In a few cases, Vladimir (Waldemar) Jochelson simply took sacred objects (so called ‘idols’) that had been standing in isolated sacred places. Here, by his own admission, is an example: “I said to the [accompanying] Yukaghir that I was planning on taking the wooden figure with me. They did not protest, although the idea clearly did not particularly please them.” (Jochelson 2005: 241 from Russian [original 1926]). While this particular figure was later lost in a murky transfer, Jochelson had reassured the wife of his Yukaghir host about it: “I told her that ‘grandfather’ would be better off with us... that he would be hanging under glass in a warm room in a great house, that he would be fed, and that people would come to see him, hanging there along with others of his kind.” (Jochelson 2005: 242 from Russian [original 1926])

Contexts for Repression

The devastation of late 19th century trade goods dependency paled in comparison to what was to come during the height of Soviet anti-religious campaigns, beginning in the late 1920s and continuing into the 1930s. A 1924 Yakutia version of Soviet laws condemning shamans typified the groundwork for repression: “Shamanism in the IaASSR is deemed an especially harmful phenomenon, undermining cultural-national rebirth and the political growth of the peoples...along with all religious cults... the activities of Shamans are thus considered to be under the jurisdiction of the criminal code of the RSFSR, for instance concerning extortion, deception for profit, ... irresponsible curing claims...”.8

Through-out the North, hundreds of shamans’ drums, cloaks and other accouterments were either collected in forced “donations” for museums in Russia, piled in storage and left to rot, or burned by over-enthusiastic activists. Some of these were young Komsomol members who were Native converts to Communism, rather than newcomer Russian revolutionaries. In response, many shamans indeed curtailed their practices, while others continued shamanic healing in secret for predominantly grateful and discrete clients. Noisy drumming, dancing and chanting in night-long seances in villages called too much attention to shamanic practice, so some seances came to be held at remote cabins and campfires in the woods. A few shamans who continued practicing were hauled off to jail, where some died. The full scope of this repression is unlikely to be known, even with open archives, for some shamans were charged with other offences, when their true “crime” was the practice of shamanism.

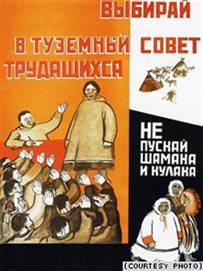

An elderly Sakha former president of the Suntar village Soviet justified the repression: “You should put this in perspective. We were doing important things in the 1930s. First there was the liquidation of illiteracy... [then the campaign] for sanitation and elementary hygiene... If shamans still tried to sneak seances with patients, or if they tried to hide their drums, then their voting rights were taken away.”9 From this kind of attitude came familiar epithets of the period, terming shamans “charlatans” or “shaman-kulaks [rich exploiters].” (See photo 4.)

Historical poster of the shaman-kulak repression campaign, from around 1931.

In the Srednaia Kolyma region, from where some of the Jesup materials come, a Sakha elder recalled:

“The main purge against shamans was in 1929. In our region, the activist Iuban Gavrilovich Tretiakov took nine drums. He then invited us, the schoolchildren of the area, to help him burn the drums. So we schoolchildren burned the drums in a big bonfire. My uncle was a shaman, and his big white drum protruded obviously from the pile. There were plenty of adults present as well as children. And many of us saw this big drum jump out from the fire. Three times the drum jumped, and three times people retrieved it and put it back on the bier.”10 The large drum may have been that of a particularly famed Sakha shaman, Tokoyeu, who at one point entrusted a drum (the same one earlier?) to his friend, the Yukaghir shaman Kurilov, probably a next generation relative of the shaman Jochelson met.

Tretiakov, after burning so many drums, was reputed to have died an unpleasant early death from a mysterious bloated stomach illness that villagers attributed to his persecution of shamans. The place where the drums had been burned later became a Soviet festival site, but that did not stop people from fearing both the site and the curses of repressed shamans.11

Such accounts help us understand both how destructive the repression was, and also why it never fully suppressed shamanists or converted believers in indigenous cosmologies to Soviet ideology. In many places, shamanic world views survived better than the shamans themselves, or their clothing and drums. Repression was hardly the most effective way to win hearts and minds in a struggle for rationality, hygiene and Soviet-style atheism.11

Contexts for (Re)Vitalization

The elder Igor Laptev, who recounted with sorrow Comrade Tretiakov’s activism and its resonance, in the post-Soviet period created an outdoor museum in his home village of Oiusardaakh, celebrating traditional Sakha culture. Throughout the Sakha Republic North, including in isolated and impoverished mixed Yukaghir, Even and Sakha villages, local enthusiasts have founded or revitalized small museums, mostly through local private donations, with displays of shamanic objects given pride of place where possible. In 1992, to coincide with the Sakha Republic’s hosting of the first international Congress on Shamanism in Yakutsk (Gogolev et al 2002), a major and dazzling exhibit of sacred objects, titled Ichchi [Spirit], was organized in the main Yaroslavski Historical Museum. Their life-sized manikin of a frightening shaman, so prominent in many Soviet period museum displays and so unlike “The Yakut Shaman’s Robe” diorama in AMNH’s Asia hall, was provided with appropriate textual context. (See photos 5 and 6.) It was surrounded by sacred objects called émégét, considered to have such spirit and vitality that visitors offered them coins. To be fair, it was possible to see the beginnings of this revitalization process in the Soviet period. For example, in 1986 an open-air museum in the Taata area, founded by the writer-elder Dmitri K. Sivtsev (Suoron Omollon), included a display of a sacred shamanic tree (called al lukh mass) placed in the center of its converted-to-a-museum Russian Orthodox church. Visitors (mostly Sakha) had placed coins, ribbons, food and other offerings on and under the tree, a practice that was condoned, if not encouraged, by the museum workers.13

: Frightening Shaman Manikin, Yaroslavski Museum diorama. Photo by M. M. Balzer, 1992, Yakutsk, Sakha Republic.

Yakut (Sakha) Shaman Curing Diorama in Asia Hall. “Yakut Shaman’s Robe” AMNH. photo archive number 5348. See also Appendix 1.

The Sakha concept of émégét can serve as a way to partially understand why objects that have been enlivened by ritual, such as rituals involving communication with spirits through the fire, continue to have power. An émégét is both the name for a spirit image, usually small wooden figures of humans or animals, and for the spirits dwelling within the figures. Some of these figures are kept and passed on in families, whether or not the families include practicing shamans. The spirits within them can be addressed with prayer for specific purposes, for example fertility as well as healing, and can be asked about the future. They can include spirits of dead family members, or spirits of virgin girls who died young,. Separate émégét are in the Jesup collection. They also can be attached (in smaller sizes, sometimes made of metal) to shamanic cloaks, especially those of female shamans, termed udagan rather than oiuun.14 (See photo 7.)

: Sakha shamanic bird figures, possibly spirit holder, émégét. AMNH catalogue number 70/9290, collected by W. Jochelson.

As shamanic objects, such as émégét, from diverse families of the North were beginning to be brought out from hiding, art historians Vladimir Ivanov-Unarov and Zina Ivanova-Unarova were able to document with increasing vigor the spiritual and artistic wealth of the applied art traditions of the peoples of Sakha Republic (Yakutia). Research, field interviews, and contact with U.S. Ambassador Jack Matlock led to their awareness of the Jesup Expedition trove of sacred and secular objects housed in the AMNH. They asked me (their frequent and grateful house guest) about the collections, and soon after received a small grant from the museum to study it in 1992. Thrilled with what they found, and with the cooperation of Laurel Kendall and her assistant, they brought back to Yakutsk slides and information. At this moment of interest in the revival of traditional culture, they gave a memorable (by all accounts) lecture in the central Yakutsk library, a main venue for Sakha intelligentsia gatherings. It and other talks stimulated elder artisans, such as Anastasiia Sivtseva, to rediscover and adapt “classic” Sakha clothing designs. Sakha began to realize that a few objects with sacred resonance thought to have been lost “even from museums” had been kept in a major international museum. (See Ivanov-Unarov and Ivanova-Unarova 2003: 336-347; Ivanova-Unarova 2000; Ivanov-Unarov and Ivanova 1998.) One was a type of ‘fur robe with inset’ kybytyylaakh son that had a sacred eagle applique, probably functioning as a protector image (See photo 8.) The whole collection and archive inspired the late Vladimir Ivanov-Unarov to receive a grant from the MacArthur Foundation to translate Jochelson’s monograph The Yukaghir and the Yukaghirized Tungus into Russian, so that indigenous peoples of the North could have greater understanding of their partially lost and imperfectly remembered cultural roots and interrelationships (Ivanov 2005: 23-25).

Sakha ‘fur robe with inset’ kybytyylaakh son, with sacred eagle applique. AMNH catalogue number 70/8525.

Both professional scholarship and touristic curiosity has in turn led other small groups of indigenous elites to visit the collections. The respectfully presented diorama of the Sakha shaman curing a patient (and not depicted as a crazy man with distorted features) has elicited particularly positive reactions.15 (See appendix 1for the text of the diorama.)

Political implications of cultural revitalization should be spelled out. The Sakha Republic today has the energetic Minister of Culture Andrei S. Borisov, the well known theatre and film director, whose ministry supports a wide network of museums with interactive cultural programs. While some in the cultural intelligentsia know about U.S. precedents concerning the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), many are busy recovering and interpreting their local material and spiritual cultural heritage. Repatriation projects have not been a priority, though responsible research certainly has. The 2009 UNESCO conference “Circumpolar Civilization in Museums of the World” may represent a new stage in awareness of collections relevant to understanding the rich history of the peoples of the Far East. Interestingly, an early query concerning the possible return of any of the AMNH collection came from the first President of Sakha Republic, Mikhail Efimevich Nikolaev, in a group interview in Yakutsk with international attendees of the conference on shamanism in 1992. He was quickly told that the collection had been acquired legally, and would be extraordinarily difficult to recover.16 Since then, the AMNH sent a small sample exhibition throughout the Far East, to help people understand the significance of their legacy collection for world history and art (Kendall 2004).

Conclusions:

Does the American Museum of Natural History cloak or harbor sacred objects from its renowned late 19th- early 20th century Jesup collection? The museum’s main role is saving objects for public marvel, rather than hiding them for posterity. Available to an increasingly multicultural audience, to cyberspace and to scholars, including indigenous Siberians eager to visit their lost heritage, these objects, very likely saved from Soviet period destruction, have become treasured symbols of a revitalizing process. Interaction with the collection on many levels has intensified in recent years.

As we study sacred objects using insights of currently active healers and patients, we can see that the elaborate cloaks of many Siberian and Far Eastern shamans reflect the values and symbols of their wearers and communities. Integrated into their suede, fringe and metallic talismans are diverse cosmologies and direct links to spirits of multiple worlds. To be effective, the cloaks are personal, constructed over a lifetime of visions and gifts from patients, and enlivened through ritual. They personify what Janet Hoskins (1998) has called a “biographical object,” and yet they are often transcendent of specific ethnic or gender identification. Their resonance enables rethinking of diverse ways spirit-imbued shamanic objects interact with believers over multiple generations. Ideas of the sacred may be fractured, nostalgic and bitter-sweet, but they can live on to potentially stimulate an awe-filled sense of the numinous, triggered by encountered objects to recover lost memories, like Marcel Proust’s famous madeléine. This may be especially the case within traditions like that of the Yukaghir, for whom belief in reincarnation is strong.

A final and dramatic interactive moment returns us to the story of the Yukaghir linguist Gavril Kurilov. When he finally stood, with reverence, over the Yukaghir cloak in the AMNH that was probably his great grandfather’s, curator Laurel Kendall explained to him (through Vladimir Ivanov-Unarov’s translation) that she had purified with incense (smudged) the precious cloak. She was concerned that its’ collector, Vladimir (Waldemar) Jochelson, had reported that the shaman had cried when he sold the cloak. Laurel told a surprised Gavril: “I prayed over it, and smudged it, using a drop cloth... I addressed the shaman: Please understand that we have treated the cloak with honor. It may be that it came to us by its destiny, and was saved because of this, from the great destruction of shamanic objects in the Soviet repressions. It has been safe with us. And now we have brought it forward at a time when the world is ready to respect you and your tradition.” Gavril simply said: “Don’t touch it. It is dangerous.”

Notes

1 See also Alexandra Konstantinovna Chirkova’s memoir (Chirkova 2005). According to Alexandra in 1993, her father’s skin suede cloak was “half Even and half Sakha” in style and symbolism. It depicts three main cosmological levels, the upper, middle and lower worlds. It includes bear and diver bird symbols, with bells, long fringe and places for three metallic sun disks, one of which is missing, possibly presented to a patient. Attached to its back is a long harness line, for the shaman’s assistant (kuturukhsut) to be able to hold on and guide the shaman during a seance. Konstantin kept his cloak with his decorated drum, drum stick, the hair of patients in a small bag, and pictures of his patients. Konstantin’s accouterments had been confiscated when he was taken to jail, but a grateful patient recovered them. For many years after his death they were held for safe-keeping by a friend of his who was a Communist Party official.

2 For more on seances and the diverse meanings behind them in Eastern Siberia, see especially Popov (2006 from ms. 1922-25); Bravina (2005); Balzer (2006, 1997, 1996a); Pentikainen et al (1998); Siikala and Hoppál (1992). On theory, compare Alfred Gell (1998) and Sherry Turkle (2007) discussing people’s culturally saturated relationship to objects. For insights into the numinous, see Turner (2006). See also Dahl and Stade (2000) for a special issue of Ethnos on museums and cultural processes; and Luke (2002) for the ways museum exhibits can become politicized.

3 For example, during research for this project, I discovered a discrepancy in the way the shamanic coat, object 70 / 5620 A, of “fur, hide, hair, sinew,” collected by W. Bogaras from Markowa village was labeled. In AMNH it is described as “Lamut (contemporary name Even),” while in Fitzhugh and Crowell (1988: 297) it is described as Yukaghir, in which case it may well have been collected by W. Jochelson.

4 Perspective on creating and transcending ethnic boundaries comes from integrating ideas of Barth (1969) and Prasenjit Duara (1995). See also Balzer (1999) for more theoretical discussion.

5 Compare Balzer (1996b); Bogaras (1904); Czapliska (1914); Saladin D’Anglure (1992); Shternberg (1999 [from AMNH ms., variation in Russian 1933]); Tedlock (2006).

6 Kendall and Krupnik (2003); Krupnik and Fitzhugh (2001). Sakha collection: 855 objects, with about 18 shamanic: here

7 Collections of St. Petersburg Tsentral’nyi gosudarstvennyi istoricheski arkhiv, TsGIA, for example fond 1264 (administration), fond 796 (church). I am especially grateful to ethnomusicologist Eduard Alekseyev and his wife Zoya for their insights into the period. Zina explains that Jochelson also bought clothing that would have been burned with its owners, but the men were lost while hunting and not given proper funerary rites. Their families were happy to take a symbolic sum and be free from the sin of destroying a beautiful and valuable object.

8 . “O merakh borby s shamanismom” Sbornik postanovlenii i rasporazhenii IaASSR 1922-26. Yaktusk, November 3, 1924.

9 Tatiana Ilichna Alekseeva, Suntar 1986 to MMB, with the help of Sakha ethnographer William Yakovlev.

10 Innokenti Feodorovich Volkhov, Srednaia Kolyma ulus 1994 to MMB.

11 Igor Semenovich Laptev, Srednaia Kolyma ulus 1994 to MMB.

12 See Balzer (2003) for more systematic analysis of the repressions, including the way degrees of repression influenced the kinds of revitalization that came in the post-Soviet period.

13 For other aspects of Sakha Republic shamanic revitalization, including the revival of seances and changes over the generations, see Balzer (2006).

14 Insights into émégét come from Alexandra Chirkova, Vera Sokolova and her mother Ekaterina Fedotovna Pavlova.

15 Some of those who have seen the AMNH exhibits, or studied the collections, besides Vladimir Ivanov-Unarov and Zina Ivanova-Unarova, and Gavril Kurilov, include (roughly in order of their visits) Anatoly Gogolev (Yakutsk State University Sakha ethnographer); Aisa Petrovna Reshetnikova (Director, Museum of Music and Folklore); Vera Solovyeva (organizer of the group Sakha Diaspora), Annya Zvereva (a Sakha artist who in 2006 also sold an object to the museum), Anastassia Bozhedonova (Sakha Republic’s Northern Forum representative in Alaska); German and Klavdia Khatylaev (Sakha musicians beginning to be know in the world music scene); Asia Gabysheva (Sakha curator of the Sakha National Art Museum); and Anatoly Alekseyev (Even professor, Yakutsk State University).

My own reaction to the text is slightly more critical. I hope in the future it can be revised to acknowledge that the contemporary, preferred ethnonational term instead of Yakut is Sakha for this farthest North of the Turkic peoples. Refinement of information about Russian Orthodoxy and ‘Russian warlords’ may also be appropriate.

16 Former president Mikhail E. Nikolaev directs the UNESCO exchange project that includes funding for the study of indigenous people’s cultural heritage, with the cooperation of museums housing Arctic collections. The 2009 Yakutsk conference is partly sponsored by this project. I hope that another product may be a catalogue in Russian and Sakha of the AMNH Jesup collection.

Appendix 1

Text for diorama “The Yakut shaman’s Robe” in AMNH. Asia Hall.

“The diorama seen here depicts a healing ceremony of the Yakut, of Eastern Siberia. This is not an imaginary re_creation but a faithful record of a ceremony held in the late nineteenth century and described by Museum anthropologist Waldemar Jochelson.

A shaman has come to heal a sick woman, whose soul has been captured by evil spirits. He has put himself into a trance by inhaling tobacco, dancing, and beating his drum. Now his soul will travel to the spirit world and do battle in order to retrieve the woman's soul and thus restore her. His assistant, on the right, holds the shaman by a chain so that if he gets lost or trapped in the spirit world he can be pulled back.

Some of the flat iron pendants on the shaman's robe might represent bird feathers, which allow the shaman's soul to fly. Iron disks symbolize aspects of his journey: the hole in the center of the one shown represents the ice hole through which he descends to the realm of evil spirits; the others represent the sun and the moon, which light his path once he is there. As the shaman dances, the noise made by these pieces and by the copper bells and rattles on the robe, as well as the sound of his drum and singing, help summon the spirits. The icon on the wall tells us that the Yakut were pressured to accept Orthodox Christianity by their Russian overlords; they nevertheless maintained their own religious practices.

Jochelson was a member of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, the Museum's first great expedition across the North Pacific rim, from the Pacific Northwest deep into Asia. The purpose of the expedition was to test the theory that Native Americans first came to North America across the Bering Strait from northeast Siberia thousands of years ago. Thanks to the work of people like Jochelson and of the many anthropologists working today, we are able to appreciate the great complexity and variety of these cultures.”